The quick-change artists

Click. When the 2,000 workers at Mohn Media start their working day, electricity is usually no more than a little “click” before the light comes on, the PC boots up and the coffee machine starts brewing. Of course, the enormous printing machines also come to life at the push of a button. But for Ralf Niediek and Burkhard Niehaus, electricity is much more than that. At Mohn Media’s own power plant, they convert natural gas to electricity and thermal energy – or to icy cold – every day. Because for the printing machines, it can never be cold enough.

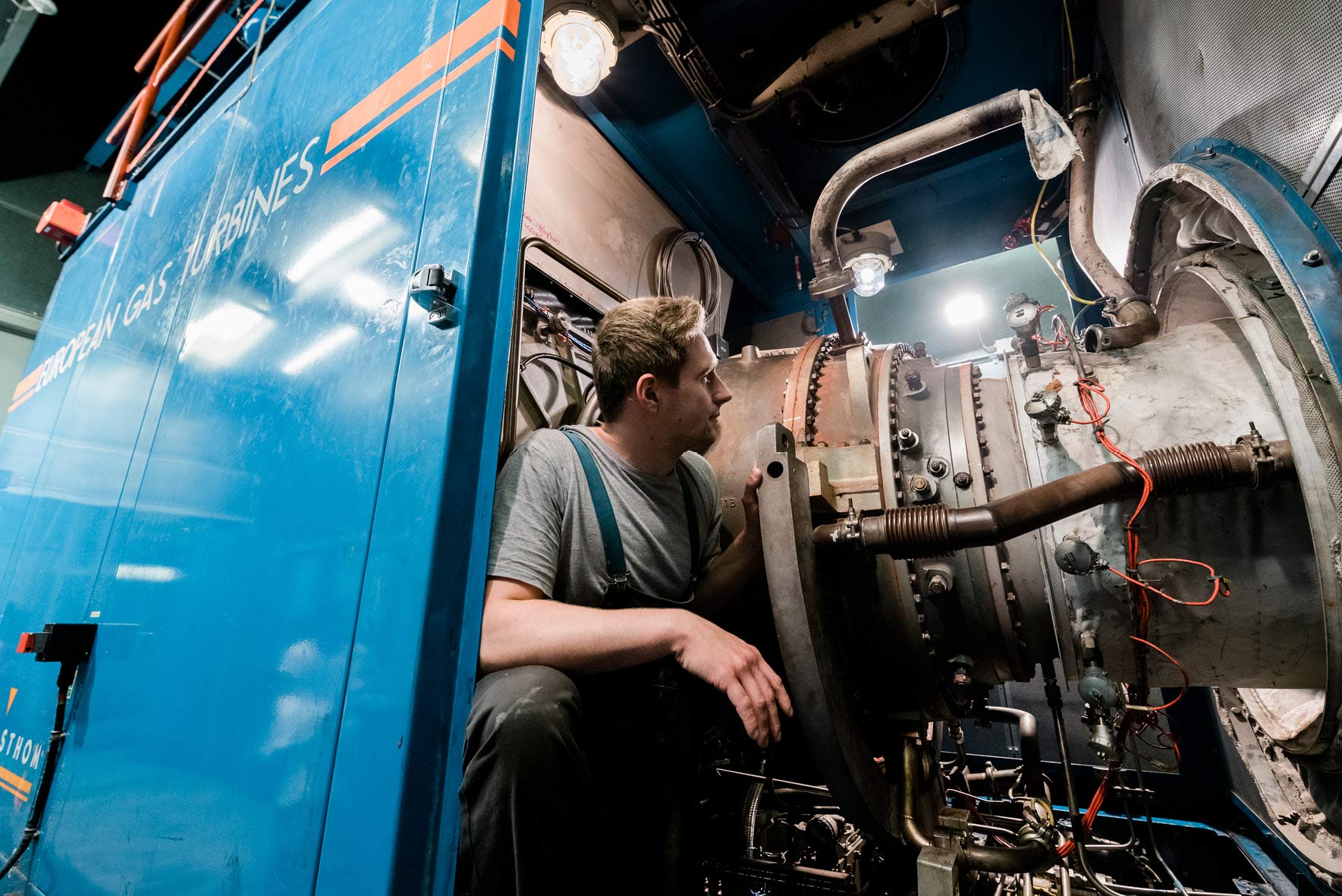

Ralf Niediek wrinkles his brow. When the Managing Director of Mohn Media Energy is standing in the machine room, he forgets everything around him. Thanks to the ear protectors he’s wearing, he can only perceive the humming of the machines through the vibrations in his chest. The 16-cylinder gas engine with a 70-litre engine capacity is one of the latest acquisitions in the energy centre. It should generate electricity even more efficiently than the older gas turbines in the neighbouring factory. Gradually, the wrinkles on his forehead smooth out; satisfied, he looks at his colleague Burkhard Niehaus and nods. The machine is running smoothly.

At the start of a new working day at Mohn Media, the two of them walk past their colleagues who work in administration and printing. Their workplace – the company’s power plant – is located far behind this, in the middle of the Gütersloh firm’s site. There, four enormous chimneys reach towards the sky; pipes extend everywhere over the area, connecting the three parts of the power plant building with each other as well as connecting the power plant with the production buildings. From the main road, the plant can hardly be seen. The imposing halls of the printing plant hide it from view. And if someone did see it flash up between the buildings, it would not occur to them that this could be a power plant. Ralf Niediek and Burkhard Niehaus often have to smile when they hear someone say that Mohn Media only prints books, newspapers or brochures. So much more than that goes on here. Here, energy is obtained efficiently in the form of heat, cold and electricity.

Much more than hot air

It was 25 years ago that someone first came up with the idea of producing electricity, heat and cold in-house. At that time, energy prices were so high that it was more economical for the company to provide its own supply. It was also more environmentally friendly to build an in-house plant, and construction therefore began shortly after the decision was made to go ahead with the project. However, it would not in fact be correct to call it a power plant in the traditional meaning of the term. Ralf Niediek is keen to point out that the in-house energy centre is a combined heat and power plant – or, as he and his colleagues call it: the CHP plant. Although the official name is unwieldy, it describes exactly what happens in the buildings behind the printing halls. The in-house power plant uses natural gas as its primary energy source and, at the same time, uses the heat that is produced during energy generation. This way, the company makes much more efficient use of the primary energy that is used. Through a gas and steam turbine plant, the centrepiece of the CHP, the company converts the heat energy that is produced during the combustion of natural gas. It thereby not only obtains electricity and heat for warming, processes and remote heating, but also absorption cooling, which is used for air conditioning in the building and to cool the printing machines. This is important, because the enormous machines need to be cooled when working at high printing speeds; otherwise, they will fail.

With the CHP we ensure that the production process runs smoothly by converting heat to cold for cooling the printing machines.

When the cat’s away, the mice will play

Burkhard Niehaus does his rounds through the plant each day to ensure the machines do not shut down, causing costly damages. The head of the power plant checks meter readings and consults with his colleagues in the control centre. As soon as one of the many lights flashes and a beeper sounds, the colleagues begin to search for the source of the error. Fortunately, serious failures occur only rarely. Usually, every problem can be solved within 15 minutes. To find out where the sticking point lies in such cases, the colleagues also call in workers in the electrical department. Together, things are faster. Such faults can sometimes also be tragic, as Burkhard Niehaus experienced for himself a few months ago. One Saturday at about nine o’clock in the morning, the system suddenly reported a problem: “Power failure across the whole site!” In a case like this, the colleagues will even come into work over Christmas or Easter to work together to get all systems and production machines ready for operation again. After the source of the fault had been located, it emerged that a mouse had run over power rails in a 10,000 Volt plant and caused a short circuit. The game of cat and mouse was over and the electrician laid the dead animal to rest.

For us, there is no such thing as a typical working day. The plant determines our daily activities.

A strong team

The constant checking of the turbines and boiler requires the men of the combined heat and power plant to always be ready. Someone is always there, even on public holidays. Over the years, the team has grown together and become a little family. Today, a team of around 7 runs the company’s in-house power plant in continuous operation. The management, as well as the energy accounting and energy management departments are run by a further three employees. If further support is needed, the electrical department and the maintenance service are also available to help. If there is a larger problem with the plant at the weekend, the colleagues are phoned and asked whether they can fill in at short notice. Within a few minutes, someone is on site and is taking care of the CHP. The team sticks together. And they do this not just for Mohn Media.

In addition to the energy for the Mohn Media, Sonopress, Corporate Centre and Foundation site, the combined heat and power plant also generates remote heating for companies located nearby such as Miele, and electricity for the town of Gütersloh. The plant has long produced more energy than Mohn Media requires. Ralf Niediek is therefore proud to call it a “little municipal utility”. For the supply of neighbouring companies, Mohn Media has set up Fernwärmegesellschaft Gütersloh (FWGG), a joint venture with the Gütersloh municipal utility. The joint enterprise is also celebrating its 25-year anniversary in 2019. A lot has happened in that time. Ralf Niediek knows that first hand. He has been taking care of the electricity supply at Mohn Media since 1986. A lot has become faster and better over the last few years; today, however, some things are also more complex and more expensive.

Keeping a close eye on things

Since the foundation stone of the power plant was laid, a number of new laws have been passed, and changed, and changed again. The team has had to regularly attend seminars and training sessions in order to adapt to the constantly changing legal framework. By now, more than 1,500 meters are installed across the whole site, and these are used to calculate energy quantities, and to identify and stop unnecessary energy consumption. Around 52 million data points are recorded each year. Holger Martin and Stephan Glasker monitor every single meter when the next electricity tax balance sheet is due. In summer, their walkarounds can be exhausting, sweaty work since the plant can reach temperatures of up to 60°C. The air is stagnant on the top floor of the three-storey-high CHP plant, and the two colleagues from the energy management department must grit their teeth. Back in the air-conditioned office, they evaluate the data, which requires not only precision, but also technical expertise. Both Ralf Niediek and Burkhard Niehaus trust their two colleagues, as they do the rest of the team. Because whether an error message has popped up in the control centre, or machine maintenance needs to be carried out, or a final report needs to be written, every colleague knows exactly what they are doing. That is important not only so that the machines at Mohn Media run smoothly, but also so that no-one has to freeze in the head office or at Miele.

The energy management system supplies us with a multitude of data points, with which we can sustainably improve our production departments and the plant’s performance.

Electricity production equals the consumption of 35,000 households

A reduction of around 50% in CO2 emissions through the combined heat and power plant, as compared with conventional electricity generation in Germany

Data points that are captured annually by the meters installed on the site: 52 million

Kilowatt hours saved through the use of cutting-edge power units in compressed air generation: 1.2 million

Years that the power plant and the Fernwärmegesellschaft (FWGG) (the joint venture with the municipal utility company) have been in operation: 25

We are cutting CO2 emissions and are already thinking of tomorrow today in many other ways.